Delta Lake essential Fundamentals: Part 2 - The DeltaLog

Multi-part series that will take you from beginner to expert in Delta Lake

In the previous part, you learned what ACID transactions are.

In this part, you will understand how Delta Transaction Log, named DeltaLog, is achieving ACID.

Transaction Log

A transaction log is a history of actions executed by a (TaDa 💡) database management system with the goal to guarantee ACID properties over a crash.

DeltaLake transaction log - DetlaLog

DeltaLog is a transaction log directory that holds an ordered record of every transaction committed on a Delta Lake table since it was created. The goal of DeltaLog is to be the single source of truth for readers who read from the same table at the same time. That means, parallel readers read the exact same data. This is achieved by tracking all the changes that users do: read, delete, update, etc. in the DeltaLog.

DeltaLog can also contain statistics on the data; depending on the type of the data/field/column, each column can have min/max values. Having this extra metadata can help with faster querying. DeltaTable read mechanism uses a simplified push down predict.

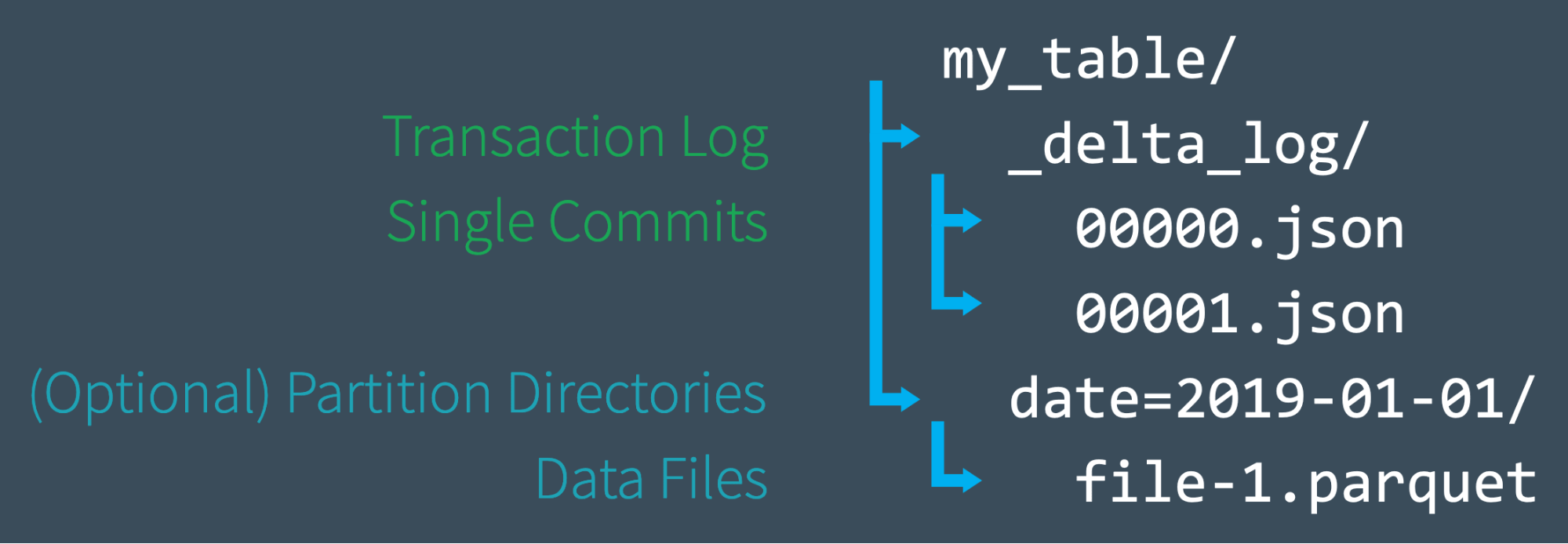

Here is a simplification of DeltaLog on the file systems from Databricks site:

The DeltaLog itself is a folder that consists of multiple JSON files. When it reaches 10 files, DeltaTable does a checkpoint and compaction operations (we will dive into it in the next chapter).

Here is an example of a DeltaLog JSON file from the code source test resources, each entry in the file is on JSON:

{"remove":{"path":"part-00001-f1cb1cf9-7a73-439c-b0ea-dcba5c2280a6-c000.snappy.parquet","dataChange":true}}

{"remove":{"path":"part-00000-f4aeebd0-a689-4e1b-bc7a-bbb0ec59dce5-c000.snappy.parquet","dataChange":true}}

There was a total of two commits captured in this file: remove -it can be a delete operation on a whole column or only specific values in it. In this operation the metadata field dataChange is set to true.

Here is a more complex JSON file example, each entry in the file is on JSON:

{"metaData":{"id":"2edf2c02-bb63-44e9-a84c-517fad0db296","format":{"provider":"parquet","options":{}},"schemaString":"{\"type\":\"struct\",\"fields\":[{\"name\":\"id\",\"type\":\"integer\",\"nullable\":true,\"metadata\":{}},{\"name\":\"value\",\"type\":\"string\",\"nullable\":true,\"metadata\":{}}]}","partitionColumns":["id"],"configuration":{}}}

{"remove":{"path":"part-00001-6d252218-2632-416e-9e46-f32316ec314a-c000.snappy.parquet","dataChange":true}}

{"remove":{"path":"part-00000-348d7f43-38f6-4778-88c7-45f379471c49-c000.snappy.parquet","dataChange":true}}

{"add":{"path":"id=5/part-00000-f1e0b560-ca00-409e-a274-f1ab264bc412.c000.snappy.parquet","partitionValues":{"id":"5"},"size":362,"modificationTime":1501109076000,"dataChange":true}}

{"add":{"path":"id=6/part-00000-adb59f54-6b8f-4bfd-9915-ae26bd0f0e2c.c000.snappy.parquet","partitionValues":{"id":"6"},"size":362,"modificationTime":1501109076000,"dataChange":true}}

{"add":{"path":"id=4/part-00001-36c738bf-7836-479b-9cc1-7a4934207856.c000.snappy.parquet","partitionValues":{"id":"4"},"size":362,"modificationTime":1501109076000,"dataChange":true}}

In this example, there is the metadata object entry - it represents a change in the table columns either an update to the table schema or that a new table was created. Later we see two remove operations, followed by three add operations. These operation objects can have a stat field, which contains statistical information, such as the number of records, minValues, maxValues, and more.

These JSON files might also contain operation objects with fields such as - “STREAMING UPDATE”, “NOTEBOOK” if the operation took place from a notebook, isolationLevel, etc.

This information is valuable for managing the table and avoiding redundant full scan on the storage.

To simplify the connection between DeltaTable and DeltaLog, it’s easier to think about DeltaTable as a direct result of a set of actions audited by the DeltaLog.

DeltaLog and Atomicity

From part one, you already know that atomicity means that a transaction, either happened or not. The DeltaLog itself consists of atomic operations; each line in the log (like the ones you saw above) represents an action, which is an atomic unit; These are called commits. The transactions that took place on the data can be broken into multiple components in which each one individually represents a commit in the DeltaLog. These breaking complex operations into small transactions help with ensuring atomicity.

DeltaLog and Isolation

Operations such as Update, Delete, Add can harm isolation; Hence, since we want to guarantee isolation with DeltaTable, readers only get access to the table snapshot. This guarantees all parallel readers read the exact data. For handling deletion operations, Delta postpones the actual delete operation on the files; it first tags the files as deleted and later, remove them when considered safe (similar to Cassandra, and ElasticSearch delete operations with a tombstone).

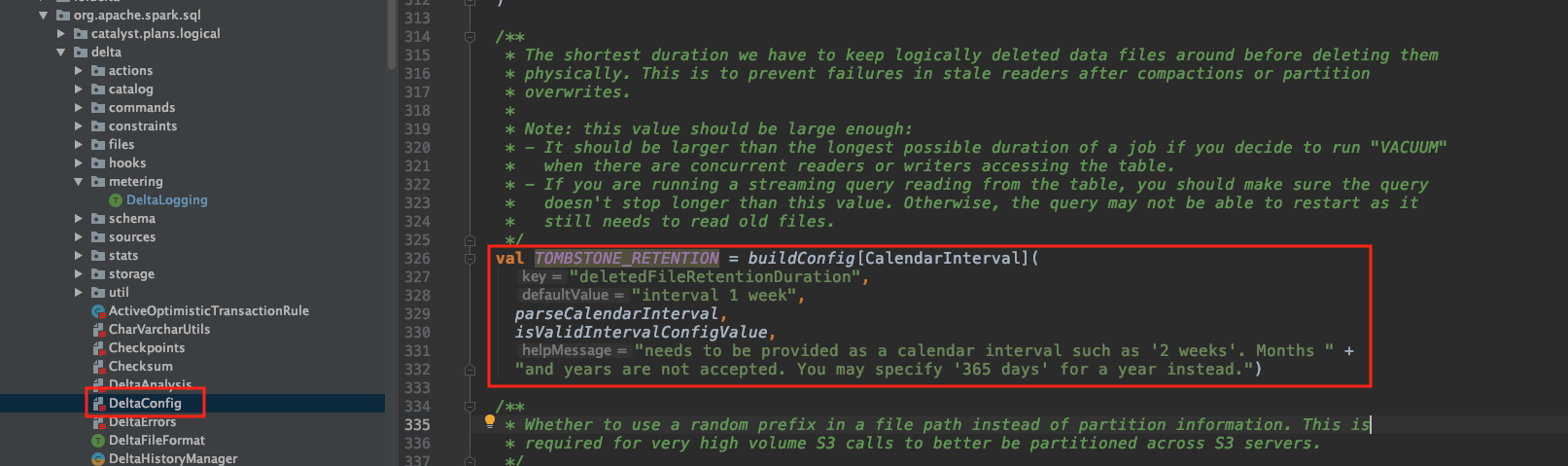

In DeltaLake 0.8.1 source code, there is a comment saying that it’s recommended to have the delete retention set to at least 2 weeks or longer than a duration of a job.

Note: This will impact streaming workload as well, because there will be a need to delete the actual files at some point, which might result in blocking the stream.

DeltaLog and Consistency

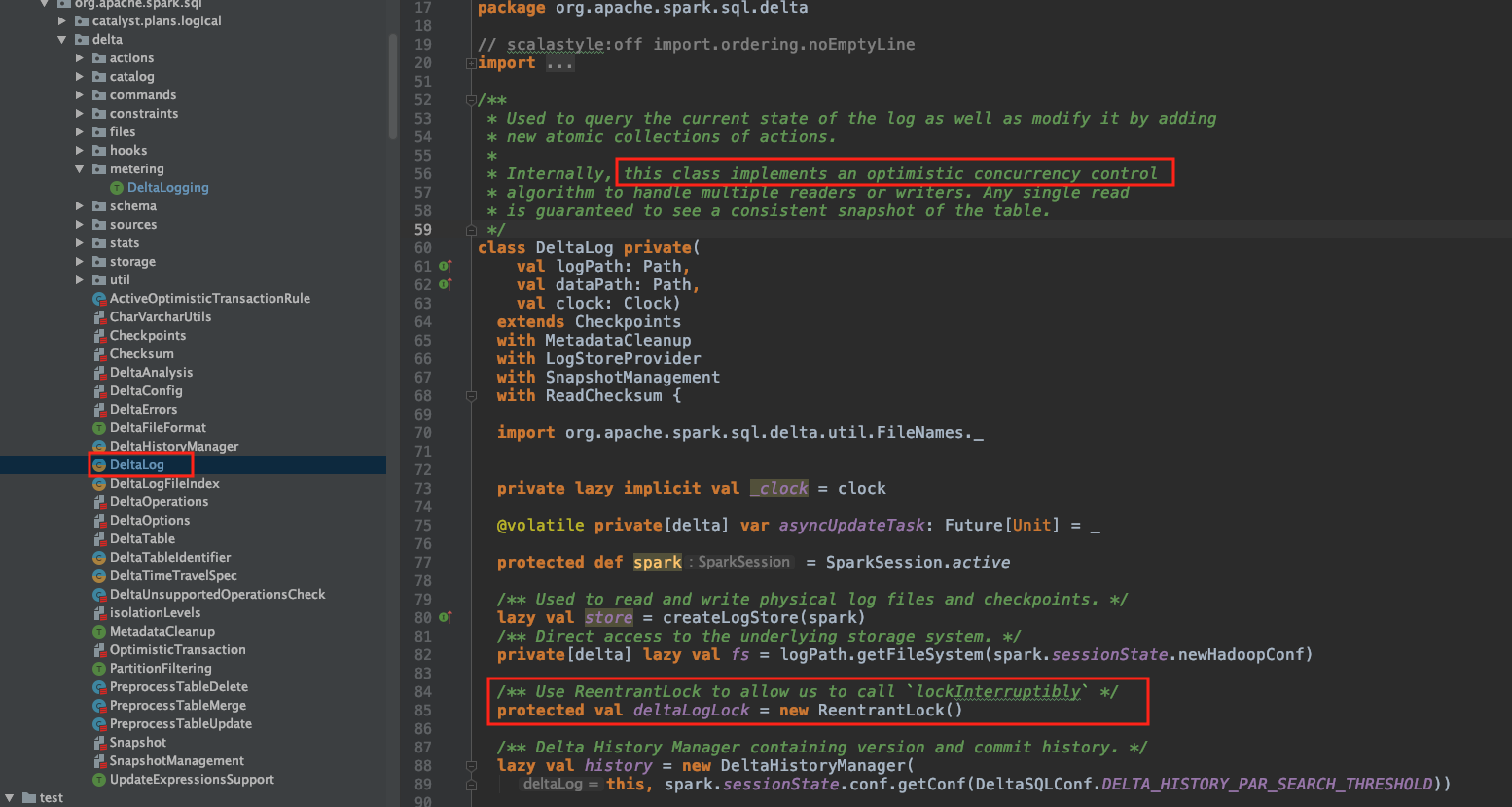

Delta Lake solves the problem of consistency by solving conflicts with an optimistic concurrency algorithm.

The class in charge of this algorithm is the OptimisticTransaction class. It achieves it by using Java 8 ReentrantLock that is controlled from a DeltaLog instance.

Here is the code snippet:

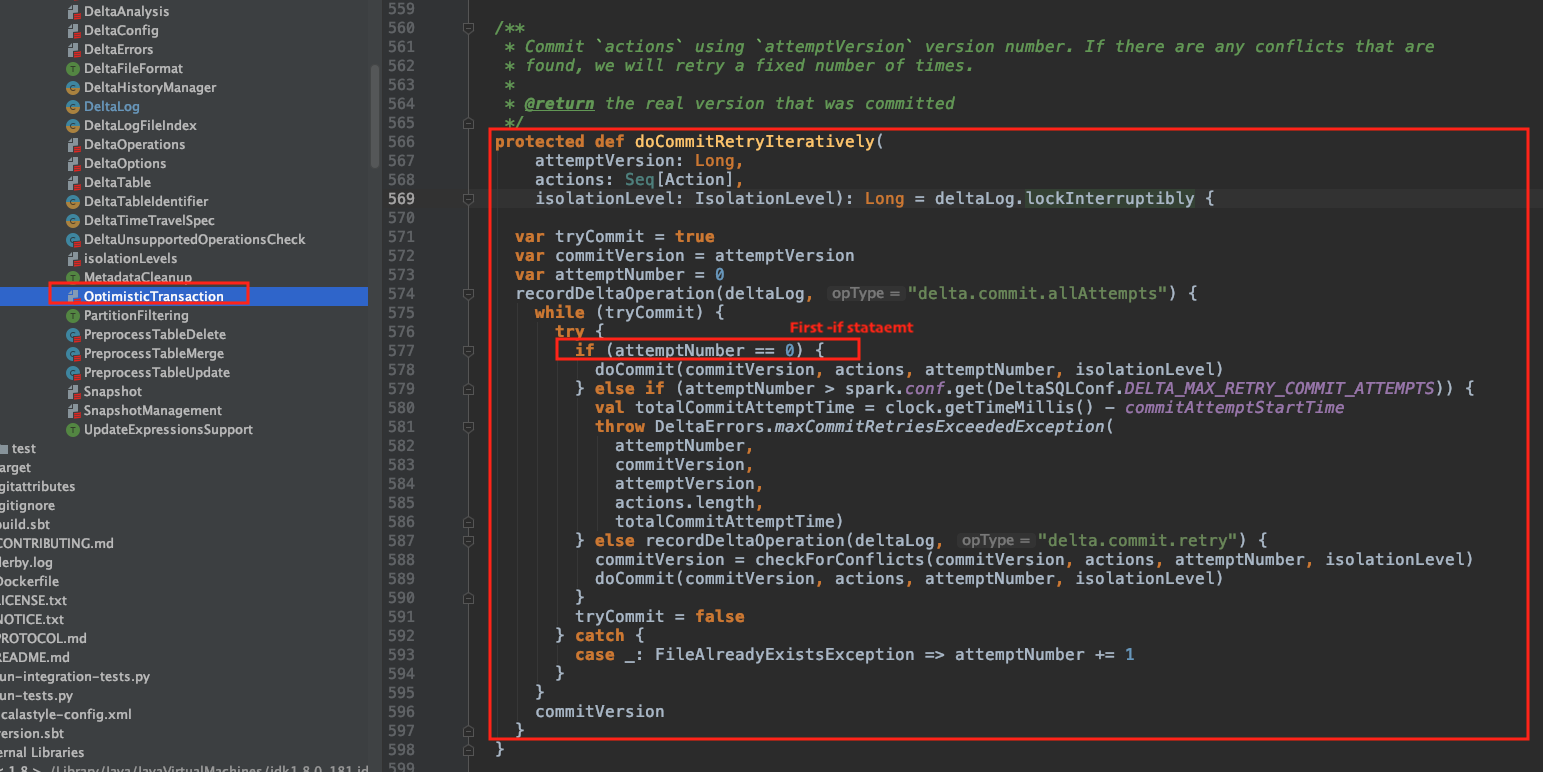

A DeltaTable instance actively uses the ReentrantLock in the OptimisticTransaction under the doCommitRetryIteratively function.

The optimistic approach was chosen here because in the big data world there is a tendency to add more data than to update existing records.

It’s rare to find and update a specific record, it is usually done when there was some data corruption on necessary data.

Here is the code snippet for the optimistic algorithm:

Notice that in line 572, the program records the attempted version as the commitVersion instance which is of type var.

var in Scala represents a mutable object instance, which means we should expect its value to change.

In line 575, we start the algorithm:

it starts the while(true) loop and maintains an attemptNumber counter; if it’s ==0, it will try to commit; if it fails here, that means that a file with this commitVersion was already written/committed into the table and it will throw an exception. That exception is being caught in lines 592+593. From there, with each failure, the algorithm is increasing the attemptNumber by 1.

After the first failure, the program won’t go into the first if statement on line 577; it will go straights into the else if on line 579.

If the program reached the state where attemptNumber is bigger than the maximum allowed/configured, it will throw a DeltaErrors.maxCommitRetriesExceededException exception.

maxCommitRetriesExceededException exception will provide information about the commit version, the first commit version attempt, the number of attempted commits, and total time spent attempting this commit in ms.

Otherwise, it will try to record this update with checkForConflict functionality in line 588.

Multiple scenarios can bring us to this state.

High-level pseudo-code:

while(tryCommit)

if first attempt:

do commit

else if: attempt number > max retries

throw an exception - exit loop

else:

record retry operation

try fixing logical conflicts - return valid commit version or throw an exception

do commit

retry on exceptions and attempt version +1

if no exception - end loop

end

To support the users, DeltaLake introduces a set of conflict exceptions that provide more information about the data and the conflicts:

Let’s look at some of the conflict scenarios.

Two Writers:

This is the case of two writers who appends data to the same table simultaneously, without reading anything. In this scenario, one writer will commit, and the second writer will read the first one’s updates before adding their own updates. Suppose it was only an append operation, like a counter which both are incrementing. In that case, there is no need to redo all computations, and it will automatically commit; if that’s not the case, writer number two will need to redo the computation given the new information from writer one.

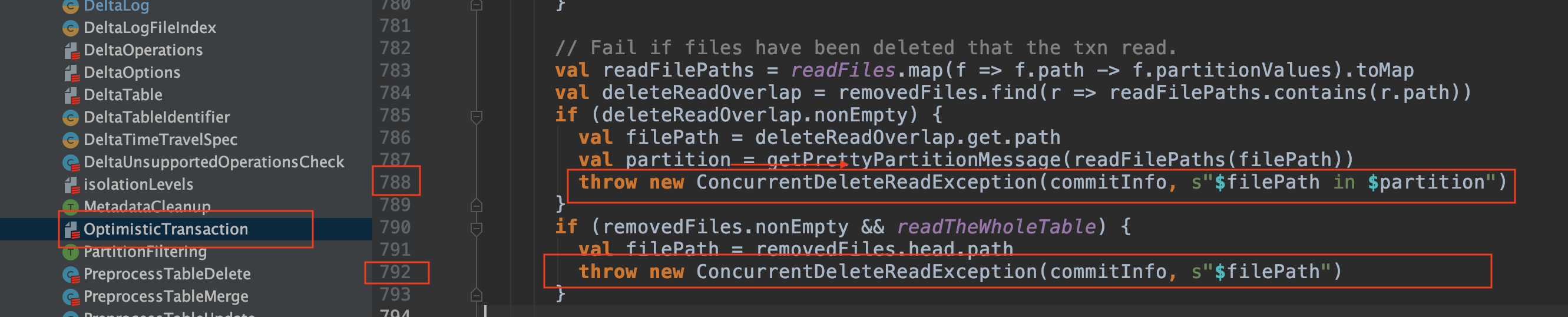

Delete and Read:

In a more complex scenario like this one, there is no automated solution. For concurrent Delete-Read, there is a dedicated ConcurentDeleteReadException.

That means that if there is a request to delete a file that at the same time is being used for a read, the program throws an exception.

Delete and Delete:

When two operations delete the same file, it might be due to a compaction mechanism or other operation, here too an exception will occur.

DeltaLog and Durability

Since all transactions made on a DeltaTable are being stored directly to the disk/file system, durability is a given. All commits are being persisted to disk. In case of a system failure, they can be restored from the disk. (Unless there is a true disaster like fire etc and damage to the actual disks holding the information).

For exploring and learning about Delta, I did a deep dive into the code source itself. If you are interested in joining me, I captured it through videos, let me know if that is useful for you.

What’s next?

Next, we will see more examples, scenarios and use cases for DeltaLake! We will learn about the compaction mechanism, schema enforcement and how it can enforce exactly once operation.

As always, I would love to get your comments and feedback on Adi Polak 🐦.

If you would like to get monthly updates, consider subscribing.